In April, Mary Elizabeth addressed traditional technology in one of our Tech Talk blog posts. Her post focused on hand planes, one of Mary Elizabeth’s (and my) favorite tools. The typical woodworker has at least four or five unique purpose planes (flattening, smoothing, shaping, profiling, etc.) of varying sizes – some so distinct from another that it is hard to reckon them to be in the same class of tools.

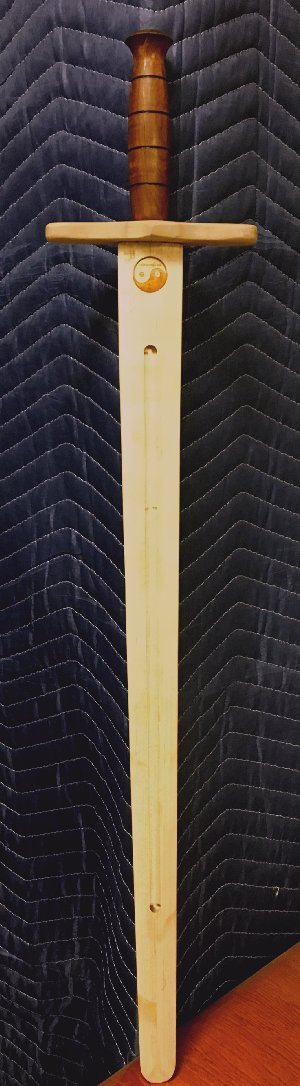

I was making a pair of replica broadswords for my son and grandson this week and – after preliminary cutting and shaping – had to refine the angles and surfaces of the swords’ blades. The right tool for this, in my mind is the lowly spokeshave and so I reached for one of mine to help me with this task. Evolving from primitive shaping tools like the draw knife and scraper, and considered to be a form of hand plane, the spokeshave has been around for eons in one form or another. Like all hand planes, a spokeshave may have a cap iron and a frog, is set up against the work with a sole , and slices off fine shavings using a fixed position blade that goes through the body. For me, that’s about where the similarities end.

I find that the spokeshave is much more versatile wherever practical, and, moreover, more tactile than typical flat-sole hand planes. This is in part because the motion is a pulling one using a set of handles at the side of the body (of course, there are many other planes that use a pulling motion). The sole may be flat, convex or concave depending on its function but, in either case, it takes practice to get the shave to address the surface for optimum effect. It also takes (and gives) a feel for the wood and the grain that is very special. When you have addressed the grain and surface well, long thin shavings feed out from the mouth of the unit with consistent dimensions, and the wood surface takes on a beautiful smoothness that is often ready for finish without any additional sanding or other surface preparation. The feel of that spokeshave slicing through the wood (as felt through those winged handles) is like no other tool I know.

Bill Howe’s presentation to the Atlantic Woodworkers’ Association in April inspired me to think about and use the spokeshave more and so I find I am increasingly going to it in projects of this nature – not only because it is an effective tool, but also because the feel of working with a spokeshave is extremely gratifying. For me there is also a sense that I am working with an ages-old technology/ tool using traditional techniques – and that, in itself, is certainly appealing.

In the current project, this sense of building and preserving tradition is even more enhanced since what I am making is a traditional weapon that dates back to the 6th century and which endured for centuries. The broadsword was used in battle by medieval knights and was considered one of the knight’s most prized assets. For training and tournaments, rebated (blunted) and wooden swords were used to limit injury and so there must have been a time when wooden swords like this were being made to closely replicate the look and feel of their iron counterparts. I can imagine some 11th century woodsmith or swordsmith sitting down to a similar task with a spokeshave or draw knife to carve those same sword facets for a Lancelot or a Galahad.

Anon, with spokeshave at hand, I must away to this labor of love.

Recent Comments